As a former clinical psychologist who now writes fiction, I’m not particularly drawn to cr ime on the page. So it was almost as much a surprise to me as to anyone that my forthcoming second novel, Underneath, is about a man who keeps a woman captive in a cellar. But, as you might expect from my mental health background, what attracts me to this topic is not the offence itself, but the character underneath it; less the what (although the novel certainly addresses that), but the how and why.

ime on the page. So it was almost as much a surprise to me as to anyone that my forthcoming second novel, Underneath, is about a man who keeps a woman captive in a cellar. But, as you might expect from my mental health background, what attracts me to this topic is not the offence itself, but the character underneath it; less the what (although the novel certainly addresses that), but the how and why.

My character Steve’s emotionally neglectful childhood has left him with abandonment issues, which he’s managed to side-step for most of his life by a peripatetic lifestyle with no expectation of forming long-term bonds. Eventually, it’s time to settle down and, as his new girlfriend moves in with him, life seems to have turned out fine. But even then there are warning signs in his defensive cognitive style. In conversation with her friend and colleague – and Steve’s nemesis – Jules, Liesel refers to Steve’s reaction to an art exhibition they’d seen together (p30):

Liesel stroked my hand. “Steve found the exhibition rather disturbing.”

“No I didn’t. I found it boring.”

“Same difference,” said Jules. “When you’re overwhelmed by emotion your mind switches itself off.”

Later, when Liesel’s priorities change, Steve rejects her attempts to talk through their differences, preferring, instead, to locate all vulnerability in her. This isn’t too difficult given her own issues with loss stemming from her mother’s suicide (p153):

Jules knows a good psychotherapist, she’d said, as if it were my mind that needed to be fixed.

Liesel’s perspective on mental health is grounded in her work as an art therapist in a forensic mental health unit. Unfortunately, although he respects her professional status, Steve disregards her expertise (p151 -2):

I felt sorry for her in a way. I imagined her spouting this nonsense in her interview and the panel covering their smirking mouths with their hands. I imagined her being ridiculed by the prosecution for trying to convince the jury that some thug hadn’t meant to throttle his wife, he was acting out some pre-conscious childhood trauma … She seemed to have rather too much in common with her patients. Fortunately, there was no hint as yet of criminality.

On visiting her workplace one lunchtime, Liesel tries to explain her therapeutic approach (and apologies to the art psychotherapists I’ve worked with for Steve’s misrepresentation of the profession). But he shows little empathy for the patients, instead envying the attention she gives them (p91-92):

“If you’ve missed out on the basics, like my patients have, you live with a yearning, an absence, whether you remember where it comes from or not.”

She was going all Freudian again. I gazed at the brown stain at the bottom of my coffee mug as I stifled a yawn.

Liesel squeezed my shoulder. “Sorry, I’m lecturing you like you’re one of my students.” She scraped back her chair. “I’m afraid you’ll have to go. It’s time for my group.”

I covered her hand with mine, imagining fucking her across the mottled table. “Let them wait.” It seemed morally offensive for a bunch of hooligans and perverts to have a woman like Liesel at their beck and call.

Advice to writers on creating an immoral character suggests being nonjudgemental and empathic, and framing the character’s behaviour as the outcome of various unfortunate events rather than a random act. It would spoil the story to give much detail about how personality combines with happenstance to make Steve a jailer, but there are parallels between my task as a writer and that of health and social care professionals working with mentally disordered offenders. Despite the disapproval and distaste one may feel for the crime that has been committed, professionals are conscious of the perpetrator’s circumstances and underlying vulnerability that have led them to cross the boundary. In a society that is often lacking in empathy for offenders, it can be hard to juggle the conflicting feelings of compassion for the person and condemnation of the crime.

I hope that mental health professionals, service users and their families with direct experiences of such services, if they should read Underneath, will consider that I’ve approached these issues respectfully. I also hope that readers without this background knowledge might be nudged a little closer towards a more compassionate perspective on the mentally disordered offender which, as a society, we urgently require.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

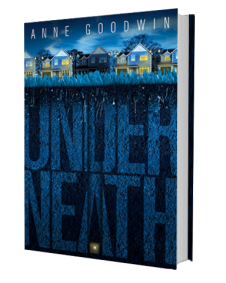

Anne Goodwin is a former employee of Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS trust. Her second novel, Underneath, is published internationally on 25th May 2017 in e-book and paperback and launched at Nottingham Writers’ Studio on 10th June.

She has contributed two previous articles to the Institute of Mental Health blog:

Three novelistic approaches to mental health issues that won’t set your teeth on edge From clinical and academic writing to fiction

Pingback: Family Dynamics: A Guest Post by Anne Goodwin, Author of Underneath | Linda's Book Bag

This is an interesting perspective on Underneath; interrogating the mental health aspect. While I haven’t yet finished reading, it is interesting to see the development of Steve’s character through his own eyes.