We all say things that we don’t mean sometimes. Perhaps the time that you snapped at the end of a long day or said that deliberately hurtful comment in the heat of an argument. Sometimes these instances are easily recognisable (perhaps easily apologised for). However, often our language conveys more subtle messages as well. Even everyday expressions may carry connotations we have not considered and speak to ideas we don’t condone. The words we use when we talk about self-harm and suicide show just that; while our language can convey compassion, provide hope, empowerment and optimism, we can also unwittingly express messages that divide and stigmatise.

I’m definitely guilty of this – while I may not like to admit it, my undergraduate notes are littered with phrases that now make me uneasy. Far from meaning to be impertinent, I was passionate about battling the silence and taboo surrounding mental health and in particular getting people talking about suicide. But, to be honest, at that point I don’t think I’d ever thought carefully about the language used when doing the talking. Then I had a conversation with a lady whose son died by suicide and realised that phrases like ‘committed suicide’ weren’t simply a case of well, it’s just what you say. For the first time I felt some of the impact of our everyday language and understood why accurate, non-stigmatised terms really matter. I’m grateful that she took the time to explain to me how challenging she found some words. That conversation prompted me to mind my ‘commits’ (‘C’s) and ‘suicides’ (‘S’s), as well as reflect further on the potential inadvertent messages conveyed by the language we choose.

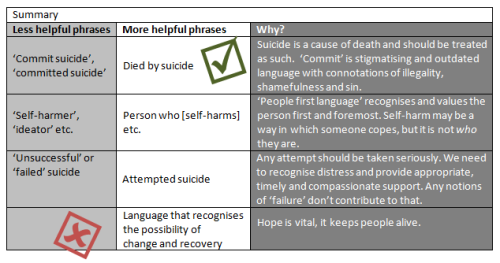

The term ‘committed suicide’ has perhaps prompted the most publicised opposition. Although commit can mean a number of things, if we think about other times we use the word, it tends to be associated with negativity and wrong-doing. People commit crimes. People commit moral atrocities. People die by suicide. While opinions about suicide vary, we don’t usually associate the term commit with a public health concern, or mental health tragedy and the phrase goes no way to acknowledging the turmoil faced by someone prior to taking their life. Historically, suicide was deemed a crime. Not anymore (not since the 1961 Suicide Act in the UK). While we’ve updated our legislation appropriately, we haven’t updated our language; suicide is a cause of death and our language should reflect this. In no other situation would we say that someone committed their death, regardless of any personal or lifestyle factors which may have contributed to the outcome.

People commit crimes.

People commit moral atrocities.

People die by suicide.

The word committed in relation to suicide is not only unnecessary, inaccurate and outdated, but for many it can be insensitive language which amplifies the distress of an already difficult situation. Those affected by suicide, whether through having experienced suicidality personally or via the experiences or loss of a loved one, are vulnerable and often stigmatised [1]. Stigmatising language with its residual connotations of illegality, shamefulness and sin only exacerbates this [2, 3].

Stigma can be life-changing and life-limiting. It reduces both the propensity to help-seek and the provision of help-giving behaviour [4]. Stigma is also faced by those who have experiences around self-harm. For some, phrases like ‘self-harmers’, ‘cutters’ and ‘ideators’ (describing people who have thought about harming themselves/taking their lives, but have not acted on these ideas) are also loaded with difficulty. Language here could be seen as dismissive and pejorative. Some feel such terms take away from individual identity; typically, self-harm affords people a means of dealing with intolerable (and often deeply distressing) emotions. It may be someone’s coping response. It is not who they are. We all hold multiple identities which intersect with each other and it is imperative that our language reflects this. Being respected and valued first and foremost as an individual is important to wellbeing and this may be especially pronounced in situations where people have traditionally been labelled, perhaps diagnosed, by others. Adopting such shorthands may be unintentionally offensive, but damaging nevertheless.

Because of this, many advocate for the use of ‘people first language’ [e.g., 5]. That is to say, to make references to ‘people who self-harm’, rather than ‘self-harmers’. Such an approach can also increase the accuracy with which we use words; unlike phrases like ‘self-harmer’, person first phrasing can easily accommodate further information regarding recency (e.g., people who have self-harmed in the last 6 months) and frequency (e.g., more than 5 times) etc. Here, language matters as it helps to shape our attitudes and ideas. Phrases that can accommodate temporal dynamics encompass notions of change and recovery. These things are really important as the possibility of change is laced with hope. And hope is vital. Hope keeps people alive.

Phrases that focus on a single behaviour, such as ‘cutter’, also present challenges to accuracy. Such terms may be seen to imply that individuals only engage in one form of self-harm. This over-simplified account might lead us to miss important details and obscure the scope of behaviours. Indeed, research shows that a change in behaviour, or engaging in multiple behaviours, is common [6]. Additionally, phrases commonly employed in medical settings, such as the term ‘deliberate’ in relation to self-harm, arguably cannot reflect the ambivalence often reported and convey unhelpful and naïve messages regarding the controllability of self-harm. This perception may lead to negative emotional responses, as well discriminatory behaviours [7].

Other common phrases that also have negative connotations include referring to non-fatal outcomes as ‘failed’ attempts and any potentially dismissive comment regarding the ‘superficial’ nature of injuries. Medical severity doesn’t tell us about the magnitude of distress [8] and crucially it is paramount that we don’t inadvertently suggest that the behaviour and associated suffering isn’t as valid. Similarly, by the logic of this language practice, to have ‘failed’ is to be alive. This is not a failure, this is an opportunity. It is important that we take any attempt seriously, that we recognise the distress and provide appropriate and timely, compassionate support. Any notions of ‘failure’ don’t contribute to that.

Of course everyone is different. People may be comfortable with different words and phrases and it’s important that individuals are free to tell their story in their own words. We can’t always anticipate what language people will be most comfortable with, but we can ensure that our words are considered and sensitive. And if we are unsure, we can ask the people we are talking to if they have preferences. We need more people discussing suicide in an informed, compassionate and open way, and we need to be clear that talking about these issues is OK and unlikely to lead to someone harming themselves [9]. By creating healthy, hopeful environments where people acknowledge emotional distress and relate sensitively about all aspects of suicide we will help to support survivors of suicide loss and help to save lives. By having an awareness of the historical context of terms, and listening to people’s feedback on language commonly employed, we can make sure our words don’t build unintentional barriers that exclude those who most need to be heard.

We have an opportunity to lead by example, to consider the choices we make and to politely and helpfully challenge those around us. We can all be part of a cultural shift. Starting with such a small and simple change, that’s quite something…

Emma Nielsen (@EmmaLNielsen) is an Associate Fellow of the Institute of Mental Health and PhD student in the School of Psychology (Lpxen@nottingham.ac.uk)

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Further information and great advice for media reporting of suicide is available from the Samaritans and Mindframe

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

If you need someone to talk to, Samaritans are available round-the-clock (and free to contact) on 116 123 (UK & ROI)

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

[1] Cvinar, J. G. (2005). Do suicide survivors suffer social stigma: A review of the literature. Perspectives in psychiatric care, 41(1), 14-21.

[2] Maple, M., Edwards, H., Plummer, D. & Minichiello, V. (2010). Silenced Voices: Hearing the stories of parents bereaved through the suicide death of a young adult child. Health and Social Care in the Community, 18(3), 241-248

[3] Sommer-Rotenberg, D. (1998). Suicide and language. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal, 159(3), 239.

[4] Reynders, A., Kerkhof, A. J. F. M., Molenberghs, G., & Van Audenhove, C. (2014). Attitudes and stigma in relation to help-seeking intentions for psychological problems in low and high suicide rate regions. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 49(2), 231-239.

[5] Guidelines on language in relation to functional psychiatric diagnosis (2015). The British Psychological Society, Division of Clinical Psychology, accessed 08-01-2016

[6] Owens, D, Kelley, R., Munyombwe, T., Bergen, H., Hawton, K., Cooper, J., Ness, J., Waters, K., West, R. & Kapur N. (2015). Switching methods of self-harm at repeat episodes: Findings from a multicentre cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 180, 44-51.

[7] Corrigan, P., Markowitz, F. E., Watson, A., Rowan, D., & Kubiak, M. A. (2003). An attribution model of public discrimination towards persons with mental illness. Journal of health and Social Behavior, 44(2),162-179.

[8] Haw, C., Hawton, K., Houston, K., & Townsend, E. (2003). Correlates of relative lethality and suicidal intent among deliberate self‐harm patients. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 33(4), 353-364.

[9] Zortea , T. (2016) Is it dangerous to ask or talk about suicide? IHAWKES (Institute of Health and Wellbeing Knowledge Exchange Students) blog, accessed 14-01-2016.

Excellent article. It’s so important to consider the language we use around mental health (indeed, all aspects of health) or we risk losing sight of the person. As health professionals we have the power to construct a person’s identity based on our choice of words – this is essential reading for anyone working with those who may self-harm or attempt suicide.

Thank you

very interested in your thoughts Nicola and people with lived experience here at MAKING WAVES and OPEN FUTURES would love to talk with you more about constructing languages of power and possibility – Julie x

Should have said Emma not Nicola!!!

Thank you for your comment Julie and glad to hear that the post was of interest to you. Would be delighted to discuss further – perhaps you could drop me an e-mail (Lpxen@nottingham.ac.uk) ?

Emma Nielsen

Hi Emma – you may find this of interest – NB link to the guidelines at the end of the release. http://news.leeds.gov.uk/journalists-and-health-workers-link-to-support-new-suicide-reporting-guidelines/

Phil

Thank you for flagging this – It is great to see the National Union of Journalists, Leeds City Council and the Strategic Suicide Prevention Group working together on such an important piece of work.

The advice certainly compliments the Mindframe and Samaritan’s media guildeines noted in the blogpost. Hopefully the ongoing efforts will ensure that reporters and editors are well equipped to make sensitive and considered choices.

Pingback: Katherine Brown – Stigma and Self-Harm: Why, and What to do? | IMH Blog (Nottingham)

Pingback: Emma Nielsen – Self Injury Awareness Day #SIAD | IMH Blog (Nottingham)

Pingback: Emma Nielsen – Media Matters: The impact of media reporting of suicide | IMH Blog (Nottingham)

Reblogged this on Far be it from me –.

My partner took his own life in January 2015 and I never found out what the real reason leading up to his death was about.

He had left us in 2012, after he took promotion at work and met new people.

He decided he didn’t want to see our young sons and me after he started working long shifts and mixing with younger people in his workplace.

In May 2014 simon asked me if he could be part of our lives again and wanted to finish all the jobs around the house and I found him a completely different person to be with.

I just could not understand why he wanted to be with us again, especially after he had told me on Christmas day in 2013 that he would rather be dead than be with me.

Simon seemed to have a time limit on everything and he wanted everything to be perfect.

He was bringing items from his home that used to belong to me and our sons, to give to my new grandson and I didn’t notice simon was emptying his home.

He had stayed friendly with my daughter and her husband and spent time with my new grandson when we met at her home for simon to spend time with out sons after he left us.

By September 2014, simon was trying to tell me he was scared of something but I couldn’t get any sense out of him.

He had been taking us on days out by the seaside and asking me what would happen to him if he fell into the deep tide, or went in the sinking sands where the cockle pickers had died in morecambe.

At the time it didn’t seem too odd because we always spent time at the seaside and people had died by accident and I thought simon was showing an interest in how things like that could happen.

If a suicide came on the news, he wanted to discuss how I felt that person was feeling and asked why I thought they would choose to end their life.

Simon asked me what I thought about parents that took their family with them in a suicide and I told him that people should never end children’s lives because they forget about adults and can adapt to people not being in their lives as they grow up.

Simon said it was because they were never going to see their family again and that is why they took them with them.

By Christmas 2014, I asked my daughter if she could help take simon to work because he was like in a trance and I couldn’t get much sense out of him.

Every time we went somewhere, simon was saying that was the last time we would be going there and if I was going to go with my sons next year.

Looking back now, everything simon did was planning for his suicide and we had some odd chats, like the ones you have with a loved one who knows they have a time limit on their life.

It was only on the day of his suicide that I found out why he had returned to us and I have never found out what really happened because of data protection laws.

I was treated as if I had mental health issues because I didn’t realise simon was suicidal but if I had known about his personal life, I would have realised what state of mind he was in.

My mental health was lied about and my daughter put my sons into care.

They now live with my sister under special guardiandhip and I am only allowed to see my sons, now aged 8 and 13, 4 times a year because of lies about simon after he ended his life.

I still have not been offered any counselling because organisations can not believe what I tell them happened after a suicude and even some mental health teams can not understand how well I am coping and they state I must be suffering from some kind of mental health issue that makes me not able to understand simon is dead.

I am still waiting for a second opinion on my mental health but no one is interested in supporting me because of lies about my mental health.

Pingback: Emma Nielsen – Media Matters: The impact of media reporting of suicide – Emma Nielsen

Pingback: The importance of starting a conversation about suicide: Advice for supporting postgraduate peers

Reblogged this on zuzusays and commented:

Thank you for this information.

Pingback: MQ Mental Health Science Meeting 2019 - Live blog - Hebden Counselling

Great post. Do you have any other ones you can drop? I like the content. :)